The blockchain concept is a fundamental component of various crypto payment methods such as Bitcoin and Ethereum. But what exactly is blockchain technology, and what other applications does this concept have? Essentially, blockchain is structured like a backward-linked list. Each element in the list points to its predecessor. So, what makes blockchain so special?

Blockchain extends the list concept by adding various constraints. One of these constraints is ensuring that no element in the list can be altered or removed. This is relatively easy to achieve using a hash function. We encode the content of each element in the list into a hash using a hash algorithm. A wide range of hash functions are now available, with SHA-512 being a current standard. This hash algorithm is already implemented in the standard library of almost every programming language and can be used easily. Specifically, this means that the SHA-512 hash is generated from all the data in a block. This hash is always unique and never occurs again. Thus, the hash serves as an identifier (ID) to locate a block. An entry in the block is a reference to its predecessors. This reference is the hash value of the predecessor, i.e., its ID. When implementing a blockchain, it is essential that the hash value of the predecessor is included in the calculation of the hash value of the current block. This detail ensures that elements in the blockchain can only be modified with great difficulty. Essentially, to manipulate the element one wishes to alter, all subsequent elements must also be changed. In a large blockchain with a very large number of blocks, such an undertaking entails an enormous computational effort that is very difficult, if not impossible, to accomplish.

This chaining provides us with a complete transaction history. This also explains why crypto payment methods are not anonymous. Even though the effort required to uniquely identify a transaction participant can be enormous, if this participant also uses various obfuscation methods with different wallets that are not linked by other transactions, the effort increases exponentially.

Of course, the mechanism just described still has significant weaknesses. Transactions, i.e., the addition of new blocks, can only be considered verified and secure once enough successors have been added to the blockchain to ensure that changes are more difficult to implement. For Bitcoin and similar cryptocurrencies, a transaction is considered secure if there are five subsequent transactions.

To avoid having just one entity storing the transaction history—that is, all the blocks of the blockchain—a decentralized approach comes into play. This means there is no central server acting as an intermediary. Such a central server could be manipulated by its operator. With sufficient computing power, this would allow for the rebuilding of even very large blockchains. In the context of cryptocurrencies, this is referred to as chain reorganization. This is also the criticism leveled at many cryptocurrencies. Apart from Bitcoin, no other decentralized and independent cryptocurrency exists. If the blockchain, with all its contained elements, is made public and each user has their own instance of this blockchain locally on their computer, where they can add elements that are then synchronized with all other instances of the blockchain, then we have a decentralized approach.

The technology for decentralized communication without an intermediary is called peer-to-peer (P2P). P2P networks are particularly vulnerable in their early stages, when there are only a few participants. With a great deal of computing power, one could easily create a large number of so-called “Zomi peers” that influence the network’s behavior. Especially in times when cloud computing, with providers like AWS and Google Cloud Platform, can provide virtually unlimited resources for relatively little money, this is a significant problem. This point should not be overlooked, particularly when there is a high financial incentive for fraudsters.

There are also various competing concepts within P2P. To implement a stable and secure blockchain, it is necessary to use only solutions that do not require supporting backbone servers. The goal is to prevent the establishment of a master chain. Therefore, questions must be answered regarding how individual peers can find each other and which protocol they use to synchronize their data. By protocol, we mean a set of rules, a fixed framework for how interaction between peers is regulated. Since this point is already quite extensive, I refer you to my 2022 presentation for an introduction to the topic.

Another feature of blockchain blocks is that their validity can be easily and quickly verified. This simply requires generating the SHA-512 hash of the entire contents of a block. If this hash matches the block’s ID, the block is valid. Time-sensitive or time-critical transactions, such as those relevant to payment systems, can also be created with minimal effort. No complex time servers are needed as intermediaries. Each block is appended with a timestamp. This timestamp must, however, take into account the location where it is created, i.e., specify the time zone. To obscure the location of the transaction participants, all times in the different time zones can be converted to the current UTC 0.

To ensure that the time is correctly set on the system, a time server can be queried for the current time when the software starts, and a correction message can be displayed if there are any discrepancies.

Of course, time-critical transactions are subject to a number of challenges. It must be ensured that a transaction was carried out within a defined time window. This is a problem that so-called real-time systems have to deal with. The double-spending problem also needs to be prevented—that is, the same amount being sent twice to different recipients. In a decentralized network, this requires confirmation of the transaction by multiple participants. Classic race conditions can also pose a problem. Race conditions can be managed by applying the Immutable design pattern to the block elements.

To prevent the blockchain from being disrupted by spam attacks, we need a solution that makes creating a single block expensive. We achieve this by incorporating computing power. The participant creating a block must solve a puzzle that requires a certain amount of computing time. If a spammer wants to flood the network with many blocks, their computing power increases exorbitantly, making it impossible for them to generate an unlimited number of blocks in a short time. This cryptographic puzzle is called a nonce, which stands for “number used only once.” The nonce mechanism in the blockchain is also often referred to as Proof of Work (POW) and is used in Bitcoin to verify the blocks by the miners.

The nonce is a (pseudo)random number for which a hash must be generated. This hash must then meet certain criteria. These could be, for example, two or three leading zeros in the hash. To prevent arbitrary hashes from being inserted into the block, the random number that solves the puzzle is stored directly. A nonce that has already been used cannot be used again, as this would circumvent the puzzle. When generating the hash from the nonce, it must meet the requirements, such as leading zeros, to be accepted.

Since finding a valid nonce becomes increasingly difficult as the number of blocks in a blockchain grows, it is necessary to change the rules for such a nonce cyclically, for example, every 2048 blocks. This also means that the rules for a valid nonce must be assigned to the corresponding blocks. Such a set of rules for the nonce can easily be formulated using a regular expression (regex).

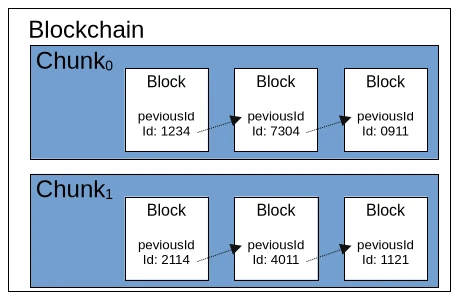

We’ve now learned a considerable amount about the ruleset for a blockchain. So it’s time to consider performance. If we were to simply store all the individual blocks of the blockchain in a list, we would quickly run out of memory. While it’s possible to store the blocks in a local database, this would negatively impact the blockchain’s speed, even with an embedded solution like SQLite. A simple solution would be to divide the blockchain into equal parts, called chunks. A chunk would have a fixed length of 2048 valid blocks, and the first block of a new chunk would point to the last block of the previous chunk. Each chunk could also contain a central rule for the nonce and store metadata such as minimum and maximum timestamps.

To briefly recap our current understanding of the blockchain ruleset, we’re looking at three different levels. The largest level is the blockchain itself, which contains fundamental metadata and configurations. Such configurations include the hash algorithm used. The second level consists of so-called chunks, which contain a defined set of block elements. As mentioned earlier, chunks also contain metadata and configurations. The smallest element of the blockchain is the block itself, which comprises an ID, the described additional information such as a timestamp and nonce, and the payload. The payload is a general term for any data object that is to be made verifiable by the blockchain. For Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, the payload is the information about the amount being transferred from Wallet A (source) to Wallet B (destination).

Blockchain technology is also suitable for many other application scenarios. For example, the hash values of open-source software artifacts could be stored in a blockchain. This would allow users to download binary files from untrusted sources and verify them against the corresponding blockchain. The same principle could be applied to the signatures of antivirus programs. Applications and other documents could also be transmitted securely in governmental settings. The blockchain would function as a kind of “postal stamp.” Accounting, including all receipts for goods and services purchased and sold, is another conceivable application.

Depending on the use case, an extension of the blockchain would be the unique signing of a block by its creator. This would utilize the classic PKI (Public Key Infrastructure) method with public and private keys. The signer stores their public key in the block and creates a signature using their private key via the payload, which is then also stored in the block.

Currently, there are two freely available blockchain implementations: BitcoinJ and Web3j for Ethereum. Of course, it’s possible to create your own universally applicable blockchain implementation using the principles just described. The pitfalls, naturally, lie in the details, some of which I’ve already touched upon in this article. Fundamentally, however, blockchain isn’t rocket science and is quite manageable for experienced developers. Anyone considering trying their hand at their own implementation now has sufficient basic knowledge to delve deeper into the necessary details of the various technologies involved.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.