You don’t have to be a software developer to recognize a good application. But from my own experience, I’ve often seen programs that were promising and innovative at the start mutate into unwieldy behemoths once they reach a certain number of users. Since I’ve been making this observation regularly for several decades now, I’ve wondered what the reasons for this might be.

The phenomenon of software programs, or solutions in general, becoming overloaded with details was termed “featuritis” by Brooks in his classic book, “The Mythical Man-Month.” Considering that the first edition of the book was published in 1975, it’s fair to say that this is a long-standing problem. Perhaps the most famous example of featureitis is Microsoft’s Windows operating system. Of course, there are countless other examples of improvements that make things worse.

The phenomenon of software programs, or solutions in general, becoming overloaded with details is what Brooks called “featuritis.” Windows users who were already familiar with Windows XP and then confronted with its wonderful successor Vista, only to be appeased again by Windows 7, and then nearly had a heart attack with Windows 8 and 8.1, were calmed down again at the beginning of Windows 10. At least for a short time, until the forced updates quickly brought them back down to earth. And don’t even get me started on Windows 11. The old saying about Windows was that every other version is junk and should be skipped. Well, that hasn’t been true since Windows 7. For me, Windows 10 was the deciding factor in completely abandoning Microsoft, and like many others, I bought a new operating system. Some switched to Apple, and those who couldn’t afford or didn’t want the expensive hardware, like me, opted for a Linux system. This shows how a lack of insight can quickly lead to the loss of significant market share. Since Microsoft isn’t drawing any conclusions from these developments, this fact seems to be of little concern to the company. For other companies, such events can quickly push them to the brink of collapse, and beyond.

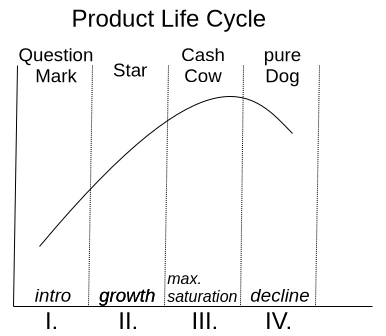

One motivation for adding more and more features to an existing application is the so-called product life cycle, which is represented by the BCG matrix in Figure 1.

With a product’s launch, it’s not yet certain whether it will be accepted by the market. If users embrace it, it quickly rises to stardom and reaches its maximum market position as a cash cow. Once market saturation is reached, it degrades to a slow seller. So far, so good. Unfortunately, the prevailing management view is that if no growth is generated compared to the previous quarter, market saturation has already been reached. This leads to the nonsensical assumption that users must be forced to accept an updated version of the product every year. Of course, the only way to motivate a purchase is to print a bulging list of new features on the packaging.

Since well-designed features can’t simply be churned out on an assembly line, a redesign of the graphical user interface is thrown in as a free bonus every time. Ultimately, this gives the impression of having something completely new, as it requires a period of adjustment to discover the new placement of familiar functions. It’s not as if the redesign actually streamlines the user experience or increases productivity. The arrangement of input fields and buttons always seems haphazardly thrown together.

But don’t worry, I’m not calling for an update boycott; I just want to talk about how things can be improved. Because one thing is certain: thanks to artificial intelligence, the market for software products will change dramatically in just a few years. I don’t expect complex and specialized applications to be produced by AI algorithms anytime soon. However, I do expect that these applications will have enough poorly generated AI-generated code sequences, which the developer doesn’t understand, injected into their codebases, leading to unstable applications. This is why I’m rethinking clean, handcrafted, efficient, and reliable software, because I’m sure there will always be a market for it.

I simply don’t want an internet browser that has mutated into a communication hub, offering chat, email, cryptocurrency payments, and who knows what else, in addition to simply displaying web pages. I want my browser to start quickly when I click something, then respond quickly and display website content correctly and promptly. If I ever want to do something else with my browser, it would be nice if I could actively enable this through a plugin.

Now, regarding the problem just described, the argument is often made that the many features are intended to reach a broad user base. Especially if an application has all possible options enabled from the start, it quickly engages inexperienced users who don’t have to first figure out how the program actually works. I can certainly understand this reasoning. It’s perfectly fine for a manufacturer to focus exclusively on inexperienced users. However, there is a middle ground that considers all user groups equally. This solution isn’t new and is very well-known: the so-called product lines.

In the past, manufacturers always defined target groups such as private individuals, businesses, and experts. These user groups were then often assigned product names like Home, Enterprise, and Ultimate. This led to everyone wanting the Ultimate version. This phenomenon is called Fear Of Missing Out (FOMO). Therefore, the names of the product groups and their assigned features are psychologically poorly chosen. So, how can this be done better?

An expert focuses their work on specific core functions that allow them to complete tasks quickly and without distractions. For me, this implies product lines like Essentials, Pure, or Core.

If the product is then intended for use by multiple people within the company, it often requires additional features such as external user management like LDAP or IAM. This specialized product line is associated with terms like Enterprise, Company, Business, and so on.

The cluttered end result, actually intended for NOOPS, has all sorts of things already activated during installation. If people don’t care about the application’s startup and response time, then go for it. Go all out. Throw in everything you can! Here, names like Ultimate, Full, and Maximized Extended are suitable for labeling the product line. The only important thing is that professionals recognize this as the cluttered version.

Those who cleverly manage these product lines and provide as many functions as possible via so-called modules, which can be installed later, enable high flexibility even in expert mode, where users might appreciate the occasional additional feature.

If you install tracking on the module system beforehand to determine how professional users upgrade their version, you’ll already have a good idea of what could be added to the new version of Essentials. However, you shouldn’t rely solely on downloads as the decision criterion for this tracking. I often try things out myself and delete extensions faster than the installation process took if I think they’re useless.

I’d like to give a small example from the DevOps field to illustrate the problem I just described. There’s the well-known GitLab, which was originally a pure code repository hosting project. The name still reflects this today. An application that requires 8 GB of RAM on a server in its basic installation just to make a Git repository accessible to other developers is unusable for me, because this software has become a jack-of-all-trades over time. Slow, inflexible, and cluttered with all sorts of unnecessary features that are better implemented using specialized solutions.

In contrast to GitLab, there’s another, less well-known solution called SCM-Manager, which focuses exclusively on managing code repositories. I personally use and recommend SCM-Manager because its basic installation is extremely compact. Despite this, it offers a vast array of features that can be added via plugins.

I tend to be suspicious of solutions that claim to be an all-in-one solution. To me, that’s always the same: trying to do everything and nothing. There’s no such thing as a jack-of-all-trades, or as we say in Austria, a miracle worker!

When selecting programs for my workflow, I focus solely on their core functionality. Are the basic features promised by the marketing truly present and as intuitive as possible? Is there comprehensive documentation that goes beyond a simple “Hello World”? Does the developer focus on continuously optimizing core functions and consider new, innovative concepts? These are the questions that matter to me.

Especially in commercial environments, programs are often used that don’t deliver on their marketing promises. Instead of choosing what’s actually needed to complete tasks, companies opt for applications whose descriptions are crammed with buzzwords. That’s why I believe that companies that refocus on their core competencies and use highly specialized applications for them will be the winners of tomorrow.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.