It’s not just high-level languages, which need to convert source code into machine code to make it executable, that require build tools. These tools are now also available for modern scripting languages like Python, Ruby, and PHP, as their scope of responsibility continues to expand. Looking back at the beginnings of this tool category, one inevitably encounters make, the first official representative of what we now call a build tool. Make’s main task was to generate machine code and package the files into a library or executable. Therefore, build tools can be considered automation tools. It’s logical that they also take over many other recurring tasks that arise in a developer’s daily work. For example, one of the most important innovations responsible for Maven’s success was the management of dependencies on other program libraries.

Another class of automation tools that has almost disappeared is the installer. Products like Inno Setup and Wise Installer were used to automate the installation process for desktop applications. These installation routines are a special form of deployment. The deployment process, in turn, depends on various factors. First and foremost, the operating system used is, of course, a crucial criterion. But the type of application also has a significant influence. Is it, for example, a web application that requires a defined runtime environment (server)? We can already see here that many of the questions being asked now fall under the umbrella of DevOps.

As a developer, it’s no longer enough to simply know how to write program code and implement functions. Anyone wanting to build a web application must first get the corresponding server running on which the application will execute. Fortunately, there are now many solutions that significantly simplify the provisioning of a working runtime. But especially for beginners, it’s not always easy to grasp the whole topic. I still remember questions in relevant forums about downloading Java Enterprise, but only finding that the application server was included.

Where automation solutions were lacking in the early 2000s, the challenge today is choosing the right tool. There’s an analogy here from the Java universe. When the Gradle build tool appeared on the market, many projects migrated from Maven to Gradle. The argument was that it offered greater flexibility. Often, the ability to define orchestrated builds was needed—that is, the sequence in which subprojects are created. Instead of acknowledging that this requirement represented an architectural shortcoming and addressing it, complex and difficult-to-manage build logic was built in Gradle. This, in turn, made customizations difficult to implement, and many projects were migrated back to Maven.

From DevOps automations, so-called pipelines have become established. Pipelines can also be understood as processes, and these processes can, in turn, be standardized. The best example of a standardized process is the build lifecycle defined in Maven, also known as the default lifecycle. This process defines 23 sequential steps, which, broadly speaking, perform the following tasks:

- Resolving and deploying dependencies

- Compiling the source code

- Compiling and running unit tests

- Packaging the files into a library or application

- Deploying the artifact locally for use in other local development projects

- Running integration tests

- Deploying the artifacts to a remote repository server.

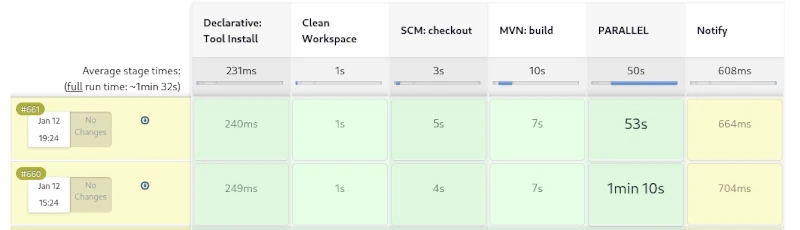

This process has proven highly effective in countless Java projects over the years. However, if you run this process as a pipeline on a CI server like Jenkins, you won’t see much. The individual steps of the build lifecycle are interdependent and cannot be triggered individually. It’s only possible to exit the lifecycle prematurely. For example, after packaging, you can skip the subsequent steps of local deployment and running the integration tests.

A weakness of the build process described here becomes apparent when creating web applications. Web frontends usually contain CSS and JavaScript code, which is also automatically optimized. To convert variables defined in SCSS into correct CSS, a SASS preprocessor must be used. Furthermore, it is very useful to compress CSS and JavaScript files as much as possible. This obfuscation process optimizes the loading times of web applications. However, there are already countless libraries for CSS and JavaScript that can be managed with the NPM tool. NPM, in turn, provides so-called development libraries like Grunt, which enable CSS processing and optimization.

We can see how complex the build process of modern applications can become. Compilation is only a small part of it. An important feature of modern build tools is the optimization of the build process. An established solution for this is creating incremental builds. This is a form of caching where only changed files are compiled or processed.

But what needs to be done during a release? This process is only needed once an implementation phase is complete, to prepare the artifact for distribution. While it’s possible to include all the steps involved in a release in the build process, this would lead to longer build times. Longer local build times disrupt the developer’s workflow, making it more efficient to define a separate process for this.

An important condition for a release is that all used libraries must also be in their final release versions. If this isn’t the case, it cannot be guaranteed that subsequent releases of this version are identical. Furthermore, all test cases must run correctly, and a failure will abort the process. Additionally, a corresponding revision tag should be set in the source control repository. The finished artifacts must be signed, and API documentation must be created. Of course, the rules described here are just a small selection, and some of the tasks can even be parallelized. By using sophisticated caching, creating a release can be accomplished quickly, even for large monoliths.

Furthermore, by utilizing sophisticated caching, creating a release can be accomplished quickly, even for large monoliths. For Maven, for example, no complete release process, similar to the build process, has been defined. Instead, the community has developed a special plugin that allows for the semi-automation of simple tasks that arise during a release.

If we take a closer look at the topic of documentation and reporting, we find ample opportunities to describe a complete process. Creating API documentation would be just one minor aspect. Far more compelling about standardized reporting are the various code inspections, some of which can even be performed in parallel.

Of course, deployment is also essential. Due to the diversity of potential target environments, a different strategy is appropriate here. One possible approach would be broad support for configuration tools like Ansible, Chef, and Puppet. Virtualization technologies such as Docker and LXC containers are also standard in the age of cloud computing. The main task of deployment would then be provisioning the target environment and deploying the artifacts from a repository server. A wealth of different deployment templates would significantly simplify this process.

If we consistently extrapolate from these assumptions, we conclude that there can be different types of projects. These would be classic development projects, from which artifacts for libraries and applications are created; test projects, which in turn contain the created artifacts as dependencies; and, of course, deployment projects for providing the infrastructure. The area of automated deployment is also reflected in the concepts of Infrastructure as Code and GitOps, which can be taken up and further developed here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.