Tag Archives: Java

Apache Maven Master Class

Apache Maven (Maven for short) was first released on March 30, 2002, as an Apache Top-Level Project under the free Apache 2.0 License. This license also allows free use by companies in a commercial environment without paying license fees.

The word Maven comes from Yiddish and means something like “collector of knowledge.”

Maven is a pure command-line program developed in the Java programming language. It belongs to the category of build tools and is primarily used in Java software development projects. In the official documentation, Maven describes itself as a project management tool, as its functions extend far beyond creating (compiling) binary executable artifacts from source code. Maven can be used to generate quality analyses of program code and API documentation, to name just a few of its diverse applications.

Benefits

- Access to all subscription articles

- Accessing the Maven Sample Git Repository

- Regular updates

- Email support

- Regular live video FAQs

- Video workshops

- Submit your own topic suggestions

- 30% discount on Maven training

Target groups

This online course is suitable for both beginners with no prior knowledge and experienced experts. Each lesson is self-contained and can be individually selected. Extensive supplementary material explains concepts and is supported by numerous references. This allows you to use the Apache Maven Master Class course as a reference. New content is continually being added to the course. If you choose to become an Apache Maven Master Class member, you will also have full access to exclusive content.

Developer

- Maven Basics

- Maven on the Command Line

- IDE Integration

- Archetypes: Creating Project Structures

- Test Integration (TDD & BDD) with Maven

- Test Containers with Maven

- Multi-Module Projects for Microservices

Build Manager / DevOps

- Release Management with Maven

- Deploy to Maven Central

- Sonatype Nexus Repository Manager

- Maven Docker Container

- Creating Docker Images with Maven

- Encrypted Passwords

- Process & Build Optimization

Quality Manager

- Maven Site – The Reporting Engine

- Determine and evaluate test coverage

- Static code analysis

- Review coding style specifications

02. Build Management & DevOps

01. Fundamentals

Index & Abbreviations

[A]

[B]

[C]

[D]

[E]

[F]

[G]

[H]

[I]

[J]

[K]

[L]

[M]

[N]

[O]

[P]

[Q]

[R]

[S]

[T]

[U]

[V]

[W]

[Y]

[Z]

[X]

return to the table of content: Apache Maven Master Class

A

- agiles Manifest

- (Apache) Ant

- Archetypen (archetypes)

B

C

D

- Deploy

- Docker Maven Image

- DRY – Don’t repeat yourself [2]

- DSL – Domain Specific Language

E

- EAR – Enterprise Archive

- EJB – Enterprise Java Beans

- Enforcer Plugin

- EoL – End of Live

F

G

- GAV Parameter [2]

- Goal [2]

- GPG – GNU Privacy Guard

H

I

- IDE – Integrierte Entwicklungsumgebung

- Installation (Linux / Windows)

- inkrementelle Builds

- (Apache) Ivy

J

- JAR – Java Archive

- jarsigner Plugin

- JDK – Java Development Kit

K

- Keytool (Java)

- KISS – Keep it simple, stupid.

- Kochbuch: Maven Codebeispiele

L

M

N

O

- OWASP – Open Web Application Security Project [2]

P

- Plugin

- Production Candidate

- POM – Project Object Model

- Maven Properties

- Prozess

Q

R

S

T

- target – Verzeichnis

- Token Replacement

U

V

W

- WAR – Web Archive

X

Y

Z

[A]

[B]

[C]

[D]

[E]

[F]

[G]

[H]

[I]

[J]

[K]

[L]

[M]

[N]

[O]

[P]

[Q]

[R]

[S]

[T]

[U]

[V]

[W]

[Y]

[Z]

[X]

return to the table of content: Apache Maven Master Class

Content | Apache Maven [en]

References & Literature

Cookbook: Maven Source Code Samples

Our Git repository contains an extensive collection of various code examples for Apache Maven projects. Everything is clearly organized by topic.

Back to table of contents: Apache Maven Master Class

- Token Replacement

- Compiler Warnings

- Excecutable JAR Files

- Enforcments

- Unit & Integration Testing

- Multi Module Project (JAR / WAR)

- BOM – Bill Of Materials (Dependency Management)

- Running ANT Tasks

- License Header – Plugin

- OWASP

- Profiles

- Maven Wrapper

- Shade Ueber JAR (Plugin)

- Java API Documantation (JavaDoc)

- Java Sources & Test Case packaging into JARs

- Docker

- Assemblies

- Maven Reporting (site)

- Flatten a POM

- GPG Signer

Blockchain – an introduction

The blockchain concept is a fundamental component of various crypto payment methods such as Bitcoin and Ethereum. But what exactly is blockchain technology, and what other applications does this concept have? Essentially, blockchain is structured like a backward-linked list. Each element in the list points to its predecessor. So, what makes blockchain so special?

Blockchain extends the list concept by adding various constraints. One of these constraints is ensuring that no element in the list can be altered or removed. This is relatively easy to achieve using a hash function. We encode the content of each element in the list into a hash using a hash algorithm. A wide range of hash functions are now available, with SHA-512 being a current standard. This hash algorithm is already implemented in the standard library of almost every programming language and can be used easily. Specifically, this means that the SHA-512 hash is generated from all the data in a block. This hash is always unique and never occurs again. Thus, the hash serves as an identifier (ID) to locate a block. An entry in the block is a reference to its predecessors. This reference is the hash value of the predecessor, i.e., its ID. When implementing a blockchain, it is essential that the hash value of the predecessor is included in the calculation of the hash value of the current block. This detail ensures that elements in the blockchain can only be modified with great difficulty. Essentially, to manipulate the element one wishes to alter, all subsequent elements must also be changed. In a large blockchain with a very large number of blocks, such an undertaking entails an enormous computational effort that is very difficult, if not impossible, to accomplish.

This chaining provides us with a complete transaction history. This also explains why crypto payment methods are not anonymous. Even though the effort required to uniquely identify a transaction participant can be enormous, if this participant also uses various obfuscation methods with different wallets that are not linked by other transactions, the effort increases exponentially.

Of course, the mechanism just described still has significant weaknesses. Transactions, i.e., the addition of new blocks, can only be considered verified and secure once enough successors have been added to the blockchain to ensure that changes are more difficult to implement. For Bitcoin and similar cryptocurrencies, a transaction is considered secure if there are five subsequent transactions.

To avoid having just one entity storing the transaction history—that is, all the blocks of the blockchain—a decentralized approach comes into play. This means there is no central server acting as an intermediary. Such a central server could be manipulated by its operator. With sufficient computing power, this would allow for the rebuilding of even very large blockchains. In the context of cryptocurrencies, this is referred to as chain reorganization. This is also the criticism leveled at many cryptocurrencies. Apart from Bitcoin, no other decentralized and independent cryptocurrency exists. If the blockchain, with all its contained elements, is made public and each user has their own instance of this blockchain locally on their computer, where they can add elements that are then synchronized with all other instances of the blockchain, then we have a decentralized approach.

The technology for decentralized communication without an intermediary is called peer-to-peer (P2P). P2P networks are particularly vulnerable in their early stages, when there are only a few participants. With a great deal of computing power, one could easily create a large number of so-called “Zomi peers” that influence the network’s behavior. Especially in times when cloud computing, with providers like AWS and Google Cloud Platform, can provide virtually unlimited resources for relatively little money, this is a significant problem. This point should not be overlooked, particularly when there is a high financial incentive for fraudsters.

There are also various competing concepts within P2P. To implement a stable and secure blockchain, it is necessary to use only solutions that do not require supporting backbone servers. The goal is to prevent the establishment of a master chain. Therefore, questions must be answered regarding how individual peers can find each other and which protocol they use to synchronize their data. By protocol, we mean a set of rules, a fixed framework for how interaction between peers is regulated. Since this point is already quite extensive, I refer you to my 2022 presentation for an introduction to the topic.

Another feature of blockchain blocks is that their validity can be easily and quickly verified. This simply requires generating the SHA-512 hash of the entire contents of a block. If this hash matches the block’s ID, the block is valid. Time-sensitive or time-critical transactions, such as those relevant to payment systems, can also be created with minimal effort. No complex time servers are needed as intermediaries. Each block is appended with a timestamp. This timestamp must, however, take into account the location where it is created, i.e., specify the time zone. To obscure the location of the transaction participants, all times in the different time zones can be converted to the current UTC 0.

To ensure that the time is correctly set on the system, a time server can be queried for the current time when the software starts, and a correction message can be displayed if there are any discrepancies.

Of course, time-critical transactions are subject to a number of challenges. It must be ensured that a transaction was carried out within a defined time window. This is a problem that so-called real-time systems have to deal with. The double-spending problem also needs to be prevented—that is, the same amount being sent twice to different recipients. In a decentralized network, this requires confirmation of the transaction by multiple participants. Classic race conditions can also pose a problem. Race conditions can be managed by applying the Immutable design pattern to the block elements.

To prevent the blockchain from being disrupted by spam attacks, we need a solution that makes creating a single block expensive. We achieve this by incorporating computing power. The participant creating a block must solve a puzzle that requires a certain amount of computing time. If a spammer wants to flood the network with many blocks, their computing power increases exorbitantly, making it impossible for them to generate an unlimited number of blocks in a short time. This cryptographic puzzle is called a nonce, which stands for “number used only once.” The nonce mechanism in the blockchain is also often referred to as Proof of Work (POW) and is used in Bitcoin to verify the blocks by the miners.

The nonce is a (pseudo)random number for which a hash must be generated. This hash must then meet certain criteria. These could be, for example, two or three leading zeros in the hash. To prevent arbitrary hashes from being inserted into the block, the random number that solves the puzzle is stored directly. A nonce that has already been used cannot be used again, as this would circumvent the puzzle. When generating the hash from the nonce, it must meet the requirements, such as leading zeros, to be accepted.

Since finding a valid nonce becomes increasingly difficult as the number of blocks in a blockchain grows, it is necessary to change the rules for such a nonce cyclically, for example, every 2048 blocks. This also means that the rules for a valid nonce must be assigned to the corresponding blocks. Such a set of rules for the nonce can easily be formulated using a regular expression (regex).

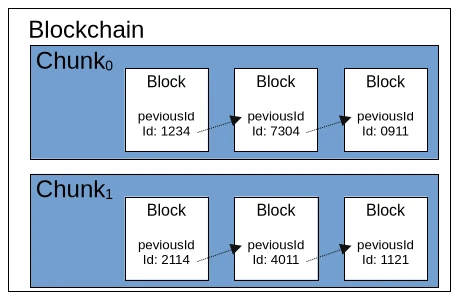

We’ve now learned a considerable amount about the ruleset for a blockchain. So it’s time to consider performance. If we were to simply store all the individual blocks of the blockchain in a list, we would quickly run out of memory. While it’s possible to store the blocks in a local database, this would negatively impact the blockchain’s speed, even with an embedded solution like SQLite. A simple solution would be to divide the blockchain into equal parts, called chunks. A chunk would have a fixed length of 2048 valid blocks, and the first block of a new chunk would point to the last block of the previous chunk. Each chunk could also contain a central rule for the nonce and store metadata such as minimum and maximum timestamps.

To briefly recap our current understanding of the blockchain ruleset, we’re looking at three different levels. The largest level is the blockchain itself, which contains fundamental metadata and configurations. Such configurations include the hash algorithm used. The second level consists of so-called chunks, which contain a defined set of block elements. As mentioned earlier, chunks also contain metadata and configurations. The smallest element of the blockchain is the block itself, which comprises an ID, the described additional information such as a timestamp and nonce, and the payload. The payload is a general term for any data object that is to be made verifiable by the blockchain. For Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, the payload is the information about the amount being transferred from Wallet A (source) to Wallet B (destination).

Blockchain technology is also suitable for many other application scenarios. For example, the hash values of open-source software artifacts could be stored in a blockchain. This would allow users to download binary files from untrusted sources and verify them against the corresponding blockchain. The same principle could be applied to the signatures of antivirus programs. Applications and other documents could also be transmitted securely in governmental settings. The blockchain would function as a kind of “postal stamp.” Accounting, including all receipts for goods and services purchased and sold, is another conceivable application.

Depending on the use case, an extension of the blockchain would be the unique signing of a block by its creator. This would utilize the classic PKI (Public Key Infrastructure) method with public and private keys. The signer stores their public key in the block and creates a signature using their private key via the payload, which is then also stored in the block.

Currently, there are two freely available blockchain implementations: BitcoinJ and Web3j for Ethereum. Of course, it’s possible to create your own universally applicable blockchain implementation using the principles just described. The pitfalls, naturally, lie in the details, some of which I’ve already touched upon in this article. Fundamentally, however, blockchain isn’t rocket science and is quite manageable for experienced developers. Anyone considering trying their hand at their own implementation now has sufficient basic knowledge to delve deeper into the necessary details of the various technologies involved.

Count on me – Java Enums

As an experienced developer, you often think that core Java topics are more for beginners. But that doesn’t necessarily have to be the case. One reason is, of course, the tunnel vision that develops in ‘pros’ over time. You can only counteract this tunnel vision by occasionally revisiting seemingly familiar topics. Unfortunately, enumerations in Java are somewhat neglected and underutilized. One possible reason for this neglect could be the many tutorials on enums available online, which only demonstrate a trivial use case. So, let’s start by looking at where enums are used in Java.

Let’s consider a few simple scenarios we encounter in everyday development. Imagine we need to implement a hash function that can support multiple hash algorithms like MD5 and SHA-1. At the user level, we often have a function that might look something like this: String hash(String text, String algorithm); – a technically correct solution.

Another example is logging. To write a log entry, the method could look like this: void log(String message, String logLevel); and examples in this style can be continued indefinitely.

The problem with this approach is free parameters like logLevel and algorithm, which allow for only a very limited number of possibilities for correct use. The risk of developers filling these parameters incorrectly under project pressure is quite high. Typos, variations in capitalization, and so on are potential sources of error. There are certainly a number of such design decisions in the Java API that could be improved.

As is often the case, there are many ways to Rome when it comes to improving the use of the API, i.e., the functions used externally. One approach that is quite common is the use of constants. To illustrate the solution a little better, I’ll take the example of hash functionality. The two hash algorithms MD5 and SHA-1 should be supported in the Hash class.

void Hash {

public final static MD5 = "1";

public final static SHA-1 = "2";

/**

* Creates a hash from text by using the chosen algorithm.

*/

public String calculateHash(String text, String algorithm) {

String hash = "";

if(algorithm.equals(MD5)) {

hash = MD5.hash(text);

}

if(algorithm.equals(SHA-1)) {

hash = SHA-1.hash(text);

}

return hash;

}

}

// Call

calculateHash("myHashValue", Hash.MD5);In the Hash class, the two constants MD5 and SHA-1 are defined to indicate which values are valid for the parameter algorithm. Developers with some experience recognize this configuration quite quickly and use it correctly. Technically, the solution is absolutely correct. However, even if something is syntactically correct, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s an optimal solution in the semantic context. The strategy presented here disregards the design principles of object-oriented programming. Although we already provide valid input values for the parameter algorithm through the constants, there’s no mechanism that enforces their use.

One might argue that this isn’t important as long as the method is called with a valid parameter. But that’s not the case. Every call to the calculateHash method without using the constants will lead to potential problems during refactoring. For example, if you want to change the value “2” to SHA-1 for consistency, this will lead to errors wherever the constants aren’t used. So, how can we improve this? The preferred solution should be the use of enums.

All enums defined in Java are derived from the class java.lang.Enum [2]. A selection of the methods is:

name()returns the name of this enum constant exactly as it appears in its enum declaration.ordinal()returns the ordinal number of this enum constant (its position in the enum declaration, with the first constant assigned ordinal number zero).toString()returns the name of this enum constant exactly as it appears in the declaration.

Dies ist die einfachste Variante, wie man ein Enum definieren kann. Eine einfache Aufzählung der gültigen Werte als Konstanten. In dieser Notation sind Konstantenname und Konstantenwert identisch. Wichtig beim Umgang mit Enums ist sich bewusst zu sein das die Namenkonventionen für Konstanten gelten.

The names of variables declared as class constants and of ANSI constants should be written exclusively in uppercase letters, with underscores (“_”) separating the words. (ANSI constants should be avoided to simplify debugging.) Example:

static final int GET_THE_CPU = 1;[1] Oracle Documentation

This property leads us to the first problem with the simplified definition of enums. If, for whatever reason, we want to define SHA-1 instead of SHA-1, this will result in an error, since “-” does not conform to the convention for constants. Therefore, the following construct is most commonly used for defining enums:

public enum HashAlgorithm {

MD5("MD5"),

SHA1("SHA-1");

private String value;

HashAlgorithm(final String value) {

this.value = value;

}

public String getValue() {

return this.value;

}

}In this example, the constant SHA1 is extended with the string value “SHA-1”. To access this value, it’s necessary to implement a way to retrieve it. This access is provided via the variable value, which has the corresponding getter getValue(). To populate the variable value, we also need a constructor. The following test case demonstrates the different ways to access the entry SHA1 and their corresponding outputs.

public class HashAlgorithmTest {

@Test

void enumNames() {

assertEquals("SHA1",

HashAlgorithm.SHA1.name());

}

@Test

void enumToString() {

assertEquals("SHA1",

HashAlgorithm.SHA1.toString());

}

@Test

void enumValues() {

assertEquals("SHA-1",

HashAlgorithm.SHA1.getValue());

}

@Test

void enumOrdinals() {

assertEquals(1,

HashAlgorithm.SHA1.ordinal());

}

}First, we access the name of the constant, which in our example is SHA1. We obtain the same result using the toString() method. We retrieve the content of SHA1, i.e., the value SHA-1, by calling our defined getValue() method. Additionally, we can query the position of SHA1 within the enum. In our example, this is the second position where SHA1 occurs, and therefore has the value 1. Let’s look at the change for enums in the implementation of the hash class from Listing 1.

public String calculateHash(String text, HashAlgorithm algorithm) {

String hash = "";

switch (algorithm) {

case MD5:

hash = MD5.hash(text);

break;

case SHA1:

hash = SHA1.hash(text);

break;

}

return hash;

}

//CaLL

calculateHash("text2hash", HashAlgorithm.MD5);In this example, we see a significant simplification of the implementation and also achieve a secure use for the algorithm parameter, which is now determined by the enum. Certainly, there are some critics who might complain about the amount of code to be written and point out that it could be done much more compactly. Such arguments tend to come from people who have no experience with large projects involving millions of lines of source code or who don’t work in a team with multiple programmers. Object-oriented design isn’t about avoiding every unnecessary character, but about writing readable, fault-tolerant, expressive, and easily modifiable code. We have covered all these attributes in this example using enums.

According to Oracle’s tutorial for Java enums [3], much more complex constructs are possible. Enums behave like Java classes and can also be enriched with logic. The specification primarily provides the compare() and equals() methods, which enable comparison and sorting. For the hash algorithm example, this functionality would not add any value. It’s also generally advisable to avoid placing additional functionality or logic within enums, as these should be treated similarly to pure data classes.

The fact that enums are indeed an important topic in Java development is demonstrated by the fact that J. Bloch dedicated an entire chapter of nearly 30 pages to them in his book “Effective Java.”

With this, we have worked through a comprehensive example of the correct use of enums and, above all, learned where this language construct finds meaningful application in Java.

Resources

Abonnement / Subscription

[English] This content is only available to subscribers.

[Deutsch] Diese Inhalte sind nur für Abonnenten verfügbar.