PDF is arguably the most important interoperable document format between operating systems and devices such as computers, smartphones, and tablets. The most important characteristic of PDF is the immutability of the documents. Of course, there are limits, and nowadays, pages can easily be removed or added to a PDF document using appropriate programs. However, the content of individual pages cannot be easily modified. Where years ago expensive specialized software such as Adobe Acrobat was required to work with PDFs, many free solutions are now available, even for commercial use. For example, the common office suites support exporting documents as PDFs.

Especially in the business world, PDF is an excellent choice for generating invoices or reports. This article focuses on this topic. I describe how simple PDF documents can be used for invoicing, etc. Complex layouts, such as those used for magazines and journals, are not covered in this article.

Technically, the freely available library openPDF is used. The concept is to generate a PDF from valid HTML code contained in a template. Since we’re working in the Java environment, Velocity is the template engine of choice. TP-CORE utilizes all these dependencies in its PdfRenderer functionality, which is implemented as a facade. This is intended to encapsulate the complexity of PDF generation within the functionality and facilitate library replacement.

While I’m not a PDF generation specialist, I’ve gained considerable experience over the years, particularly with this functionality, in terms of software project maintainability. I even gave a conference presentation on this topic. Many years ago, when I decided to support PDF in TP-CORE, the only available library was iText, which at that time was freely available with version 5. Similar to Linus Torvalds with his original source control management system, I found myself in a similar situation. iText became commercial, and I needed a new solution. Well, I’m not Linus, who can just whip up Git overnight, so after some waiting, I discovered openPDF. OpenPDF is a fork of iText 5. Now I had to adapt my existing code accordingly. This took some time, but thanks to my encapsulation, it was a manageable task. However, during this adaptation process, I discovered problems that were already causing me difficulties in my small environment, so I released TP-CORE version 3.0 to achieve functional stability. Therefore, anyone using TP-CORE version 2.x will still find iText5 as the PDF solution. But that’s enough about the development history. Let’s look at how we can currently generate PDFs with TP-CORE 3.1. Here, too, my main goal is to achieve the highest possible compatibility.

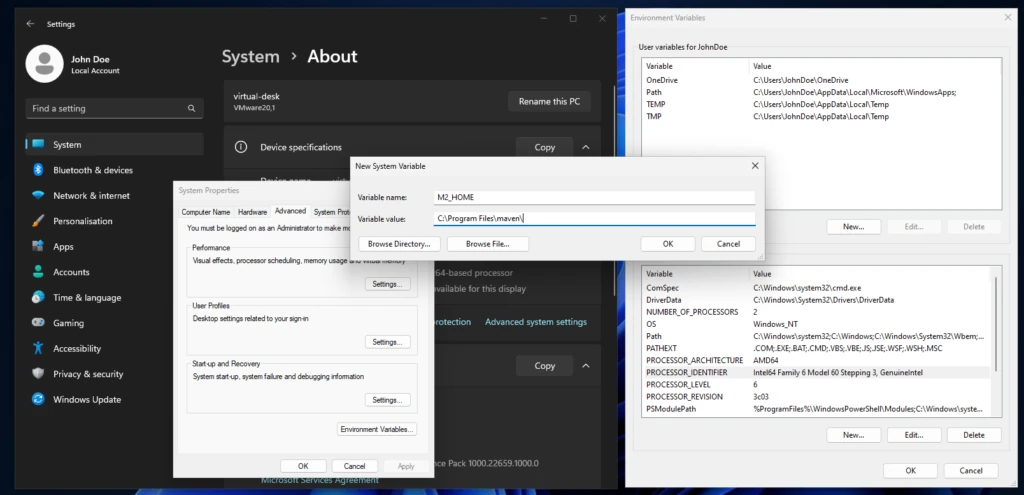

Before we can begin, we need to include TP-CORE as a dependency in our Java project. This example demonstrates the use of Maven as the build tool, but it can easily be switched to Gradle.

<dependency>

<groupId>io.github.together.modules</groupId>

<artifactId>core</artifactId>

<version>3.1.0</version>

</dependency>

To generate an invoice, for example, we need several steps. First, we need an HTML template, which we create using Velocity. The template can, of course, contain placeholders for names and addresses, enabling mail merge and batch processing. The following code demonstrates how to work with this.

<h1>HTML to PDF Velocity Template</h1>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur sadipscing elitr, sed diam nonumy eirmod tempor invidunt ut labore et dolore magna aliquyam erat, sed diam voluptua. At vero eos et accusam et justo duo dolores et ea rebum. Stet clita kasd gubergren, no sea takimata sanctus est Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</p>

<p>Duis autem vel eum iriure dolor in hendrerit in vulputate velit esse molestie consequat, vel illum dolore eu feugiat nulla facilisis at vero eros et accumsan et iusto odio dignissim qui blandit praesent luptatum zzril delenit augue duis dolore te feugait nulla facilisi. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat.</p>

<h2>Lists</h2>

<ul>

<li><b>bold</b></li>

<li><i>italic</i></li>

<li><u>underline</u></li>

</ul>

<ol>

<li>Item</li>

<li>Item</li>

</ol>

<h2>Table 100%</h2>

<table border="1" style="width: 100%; border: 1px solid black;">

<tr>

<td>Property 1</td>

<td>$prop_01</td>

<td>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet,</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Property 2</td>

<td>$prop_02</td>

<td>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet,</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Property 3</td>

<td>$prop_03</td>

<td>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet,</td>

</tr>

</table>

<img src="path/to/myImage.png" />

<h2>Links</h2>

<p>here we try a simple <a href="https://together-platform.org/tp-core/">link</a></p>template.vm

The template contains three properties: $prop_01, $prop_02, and $prop_03, which we need to populate with values. We can do this with a simple HashMap, which we insert using the TemplateRenderer, as the following example shows.

Map<String, String> properties = new HashMap<>();

properties.put("prop_01", "value 01");

properties.put("prop_02", "value 02");

properties.put("prop_03", "value 03");

TemplateRenderer templateEngine = new VelocityRenderer();

String directory = Constraints.SYSTEM_USER_HOME_DIR + "/";

String htmlTemplate = templateEngine

.loadContentByFileResource(directory, "template.vm", properties);The TemplateRenderer requires three arguments:

- directory – The full path where the template is located.

- template – The name of the Velocity template.

- properties – The HashMap containing the variables to be replaced.

The result is valid HTML code, from which we can now generate the PDF using the PdfRenderer. A special feature is the constant SYSTEM_USER_HOME_DIR, which points to the user directory of the currently logged-in user and handles differences between operating systems such as Linux and Windows.

PdfRenderer pdf = new OpenPdfRenderer();

pdf.setTitle("Title of my own PDF");

pdf.setAuthor("Elmar Dott");

pdf.setSubject("A little description about the PDF document.");

pdf.setKeywords("pdf, html, openPDF");

pdf.renderDocumentFromHtml(directory + "myOwn.pdf", htmlTemplate);The code for creating the PDF is clear and quite self-explanatory. It’s also possible to hardcode the HTML. Using the template allows for a separation of code and design, which also makes later adjustments flexible.

The default format is A4 with the dimensions size: 21cm 29.7cm; margin: 20mm 20mm; and is defined as inline CSS. This value can be customized using the setFormat(String format); method. The first value represents the width and the second value the height.

The PDF renderer also allows you to delete individual pages from a document.

PdfRenderer pdf = new OpenPdfRenderer();

PdfDocument original = pdf.loadDocument( new File("document.pdf") );

PdfDocument reduced = pdf.removePage(original, 1, 5);

pdf.writeDocument(reduced, "reduced.pdf");We can see, therefore, that great emphasis was placed on ease of use when implementing the PDF functionality. Nevertheless, there are many ways to create customized PDF documents. This makes the solution of defining the layout via HTML particularly appealing. Despite the PdfRenderer’s relatively limited functionality, Java’s inheritance mechanism makes it very easy to extend the interface and its implementation with custom solutions. This possibility also exists for all other implementations in TP-CORE.

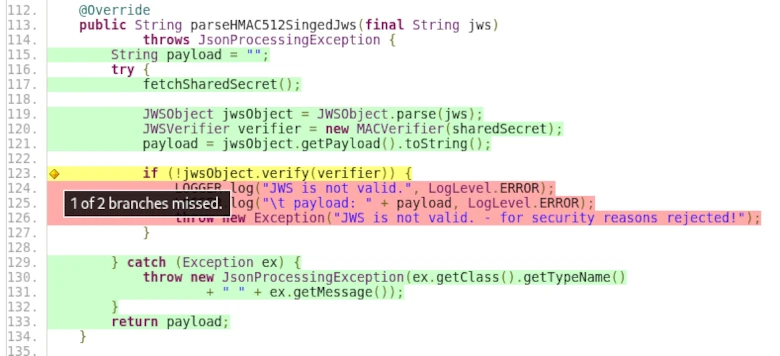

TP-CORE is also free for commercial use and has no restrictions thanks to the Apache 2 license. The source code can be found at https://git.elmar-dott.com and the documentation, including security and test coverage, can be found at https://together-platform.org/tp-core/.