Anyone interested in this somewhat specialized article doesn’t need an explanation of what Docker is and what this virtualization tool is used for. Therefore, this article is primarily aimed at system administrators, DevOps engineers, and cloud developers. For those who aren’t yet completely familiar with the technology, I recommend our Docker course: From Zero to Hero.

In a scenario where we regularly create new Docker images and instantiate various containers, our hard drive is put under considerable strain. Depending on their complexity, images can easily reach several hundred megabytes to gigabytes in size. To prevent creating new images from feeling like downloading a three-minute MP3 with a 56k modem, Docker uses a build cache. However, if there’s an error in the Dockerfile, this build cache can become quite bothersome. Therefore, it’s a good idea to clear the build cache regularly. Old container instances that are no longer in use can also lead to strange errors. So, how do you keep your Docker environment clean?

While docker rm <container-nane> and docker rmi <image-id> will certainly get you quite far, in build environments like Jenkins or server clusters, this strategy can become a time-consuming and tedious task. But first, let’s get an overview of the overall situation. The command docker system df will help us with this.

root:/home# docker system df

TYPE TOTAL ACTIVE SIZE RECLAIMABLE

Images 15 9 5.07GB 2.626GB (51%)

Containers 9 7 11.05MB 5.683MB (51%)

Local Volumes 226 7 6.258GB 6.129GB (97%)

Build Cache 0 0 0B 0BBefore I delve into the details, one important note: The commands presented are very efficient and will irrevocably delete the corresponding areas. Therefore, only use these commands in a test environment before using them on production systems. Furthermore, I’ve found it helpful to also version control the commands for instantiating containers in your text file.

The most obvious step in a Docker system cleanup is deleting unused containers. Specifically, this means that the delete command permanently removes all instances of Docker containers that are not running (i.e., not active). If you want to perform a clean slate on a Jenkins build node before deployment, you can first terminate all containers running on the machine with a single command.

Abonnement / Subscription

[English] This content is only available to subscribers.

[Deutsch] Diese Inhalte sind nur für Abonnenten verfügbar.

The -f parameter suppresses the confirmation prompt, making it ideal for automated scripts. Deleting containers frees up relatively little disk space. The main resource drain comes from downloaded images, which can also be removed with a single command. However, before images can be deleted, it must first be ensured that they are not in use by any containers (even inactive ones). Removing unused containers offers another practical advantage: it releases ports blocked by containers. A port in a host environment can only be bound to a container once, which can quickly lead to error messages. Therefore, we extend our script to include the option to delete all Docker images not currently used by containers.

Abonnement / Subscription

[English] This content is only available to subscribers.

[Deutsch] Diese Inhalte sind nur für Abonnenten verfügbar.

Another consequence of our efforts concerns Docker layers. For performance reasons, especially in CI environments, you should avoid using them. Docker volumes, on the other hand, are less problematic. When you remove the volumes, only the references in Docker are deleted. The folders and files linked to the containers remain unaffected. The -a parameter deletes all Docker volumes.

docker volume prune -a -f

Another area affected by our cleanup efforts is the build cache. Especially if you’re experimenting with creating new Dockerfiles, it can be very useful to manually clear the cache from time to time. This prevents incorrectly created layers from persisting in the builds and causing unusual errors later in the instantiated container. The corresponding command is:

docker buildx prune -f

The most radical option is to release all unused resources. There is also an explicit shell command for this.

docker volume prune -a -f

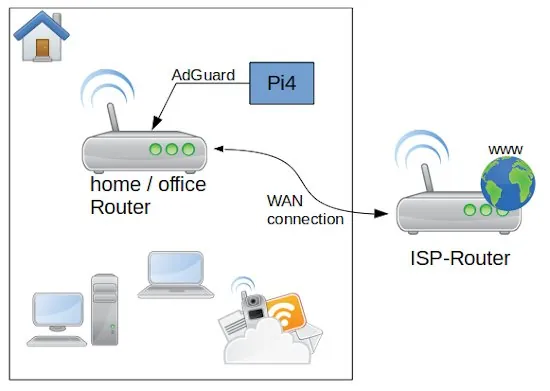

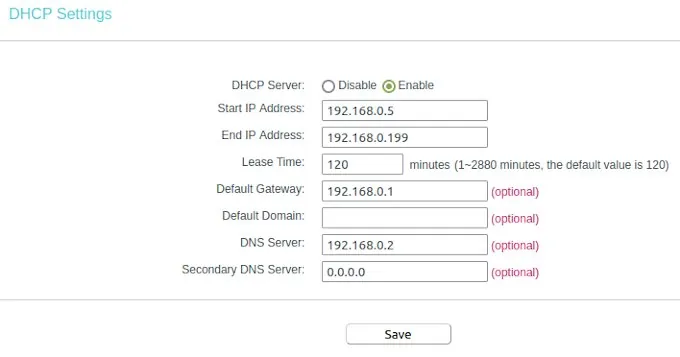

We can, of course, also use the commands just presented for CI build environments like Jenkins or GitLab CI. However, this might not necessarily lead to the desired result. A proven approach for Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment is to set up your own Docker registry where you can deploy your self-built images. This approach provides a good backup and caching system for the Docker images used. Once correctly created, images can be conveniently deployed to different server instances via the local network without having to constantly rebuild them locally. This leads to a proven approach of using a build node specifically optimized for Docker images/containers to optimally test the created images before use. Even on cloud instances like Azure and AWS, you should prioritize good performance and resource efficiency. Costs can quickly escalate and seriously disrupt a stable project.

In this article, we have seen that in-depth knowledge of the tools used offers several opportunities for cost savings. The motto “We do it because we can” is particularly unhelpful in a commercial environment and can quickly degenerate into an expensive waste of resources.