The cloud is one of the most innovative developments since the turn of the millennium and enables us to make widespread use of neural networks, which we popularly refer to as Large Language Models (LLM). This technological leap can only be surpassed by quantum computing. But enough of the buzzwords for SEO optimization, instead let’s take a look behind the scenes. Let’s start with what the cloud actually is and put all the marketing terms aside.

The best way to imagine the cloud is as a gigantic supercomputer made up of many small computers like building blocks. This theoretically allows you to combine any amount of CPU power, RAM and hard drive space. On this supercomputer, which runs in a data center, virtual machines can now be provided that simulate a real computer with freely definable hardware. In this way, the physical hardware resources can be optimally distributed among the provided virtual machines.

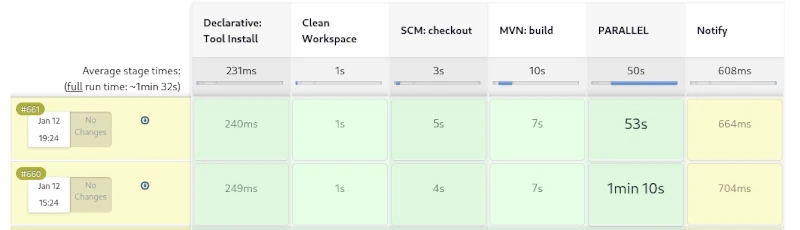

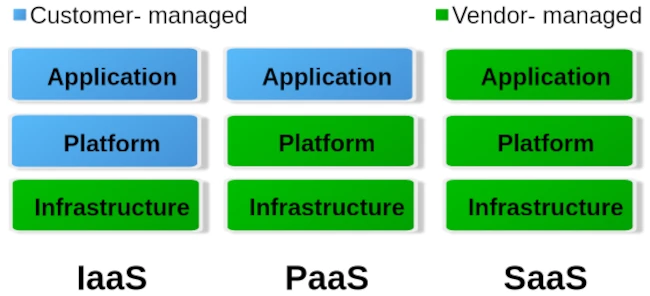

When it comes to cloud, we roughly distinguish between three different operating levels: Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS) and Software as a Service. The image below gives an idea of how these levels are divided.

To put it simply, you can say that with IaaS the provider only provides the hardware specification. So CPU, RAM, hard drive and internet connection. Via the administration software e.g. B. Kubernetes, you can now create your own virtual machines/containers and install the corresponding operating systems and services yourself. The entire responsibility for security and network routing lies with the customer. PaaS, on the other hand, already provides a rudimentary virtual machine including the selected operating system. What you ultimately install on this system above the operating system level is up to you. But here too, the issue of security is largely in the hands of the customer. For most hosting providers, typical PaaS products are so-called virtual servers. Users have the least freedom with SaaS. Here you usually only have permission to use software through a user account. Very typical SaaS products are email accounts, but also so-called managed servers. Managed servers are mostly used to provide your own websites. Here the version of the programming language and the database is specified by the server operator.

Managed servers in particular have a long tradition. They emerged at the turn of the millennium to provide an immediately usable environment for dynamic PHP websites with a MySQL database connection. The situation is similar with the serverless products that have recently become fashionable. Depending on your level of experience, you can now buy corresponding products from the major providers AWS, Google and Microsoft Azure.

The idea is to no longer operate your own servers for the services and thus outsource the entire hardware, operation and security effort to the cloud operators. In principle, this isn’t a bad idea, especially when it comes to small companies or startups that don’t have a lot of financial resources at their disposal or simply lack the administrative know-how for networks, Linux and server security.

Of course, serverless offerings that are completely managed externally quickly reach their limits. Especially if you want to provide your own developed individual serverless software in the cloud with as little effort as possible, you will come across many a stumbling block. A problem is often the flexible expandability when requirements change. You can certainly buy products from the various providers’ portfolios and combine them as you like like a building block set, but the costs incurred can quickly add up.

Basically, there is nothing wrong with a pay per use model (i.e. pay for what you use). At first glance, this is not a bad solution for people and organizations with small budgets. But here too, it’s the little details that can quickly grow into serious problems.

If you choose any cloud provider, you are well advised to avoid its proprietary management and automation products and instead use established general products if possible. If you commit yourself to one provider with all the consequences, it will only be possible to switch to another provider with great effort. Changes to the terms and conditions or continuously increasing costs are possible reasons for a forced change. Therefore, test whoever binds himself forever.

But also careless use of resources in cloud systems, e.g. B. due to incorrect configurations or unfavorable deployment strategies, can lead to an explosion in costs. Here you are well advised if there is the option to set limits and activate them. So that once you reach a certain amount, you will be informed that only a ‘certain’ quota is available. Especially with highly available services that suddenly receive an enormous number of new users, such limits can quickly lead to them being disconnected from the network. It is therefore always a good idea to use two cloud solutions, one for development and a separate one for the productive system, in order to minimize the offline risk.

Similar to stock market trading, you can also define limits for cloud services like AWS. Stop-loss orders on the stock market prevent you from selling a stock too cheaply or buying it too expensively. With the pay-per-use model, it’s not much different in the cloud. Here, you need to set appropriate limits with your provider to prevent bills from exceeding your available budget. These limits are also dynamic in the cloud. This means that the framework conditions are constantly changing, requiring the necessary limits to be regularly adjusted to meet current needs. To identify bottlenecks early, a robust monitoring system should be in place. The minimum requirement for an AWS node is determined by its requests. The upper limit of available resources is defined by the limit. Tools like IBM’s Kubecost can largely automate cost monitoring in Kubernetes clusters.

For cloud development environments, you should also keep a close eye on your own development and DevOps team. If an NPM Docker container of over 2 GB is created on the fly every time for a simple JavaScript Angular app, this strategy should definitely be questioned. Even if the cloud can allocate seemingly infinite resources dynamically, that doesn’t mean that this happens for free.

Of course, the issue of security is also an important factor. Of course, you can trust the cloud operator when he says that everything is encrypted and access to customer data and business secrets is not possible. One can certainly assume that the information that is to be accessed in most ventures rarely has any exciting or even exciting content that could be of interest to large cloud operators. If you still want to be on the safe side, you should write off the idea of serverless completely and consider running your own cloud. Thanks to modern and free software, this is now easier than expected.

I have learned from personal experience that, given the complexity of modern web applications, efficient monitoring with Grafana and Prometheus or other solutions such as the ELK Stack or Slunk is essential. But some DevOps teams have difficulties with data collection and proper evaluation. IT decision-makers in particular are asked to get a technical overview so as not to fall for the well-sounding marketing traps of cloud and serverless.